Im Mittelalter wurde das Salzwasser in den Salzpfannen der Siedehäuser erhitzt, bis das Wasser verdampft war und nur noch das Salz übrig blieb. Die Salzmeister, sogenannte Sülfmeister, überwachten die Gewinnung und waren hoch angesehen.

Das Salz tritt übrigens noch heute in Form einer Salzwasserquelle aus dem Boden und das Thema "Salz" ist in der ganzen Stadt noch allgegenwärtig.

Lesen Sie hier die Geschichte, wie das Salz entdeckt wurde:

Vor mehr als 1000 Jahren gab es rund um Lüneburg viel Wald und Morast.

Zwei Jäger waren auf der Jagd nach einer Wildsau, die sich im Schlamm wälzte. Sie lauerten der Sau auf und wollten sie erlegen, doch es gelang ihnen nicht. Das Tier konnte waidwund durch den Dickicht des Waldes flüchten. Sofort verfolgten die Jäger die Fährte des angeschossenen Tiers.

Auf einer Lichtung erblickten sie die Sau, tot in der Sonne liegend. Sie glaubten an ein Wunder, denn die Borsten des Wildschweins waren schneeweiß geworden.

Sie traten heran und befühlten das sonderbar in der Sonne glänzende Fell. Die Jäger merkten, dass die Borsten des Wildschweins voller Salzkristalle waren.

Zurück an der Ausgangsstelle ihrer Jagd, wo sich die Sau im Morast gesuhlt hatte, probierten sie das Wasser und stellten fest, dass es salzig war.

So wurde der erste Salztümpel gefunden, die spätere Solequelle der Lüneburger Saline.

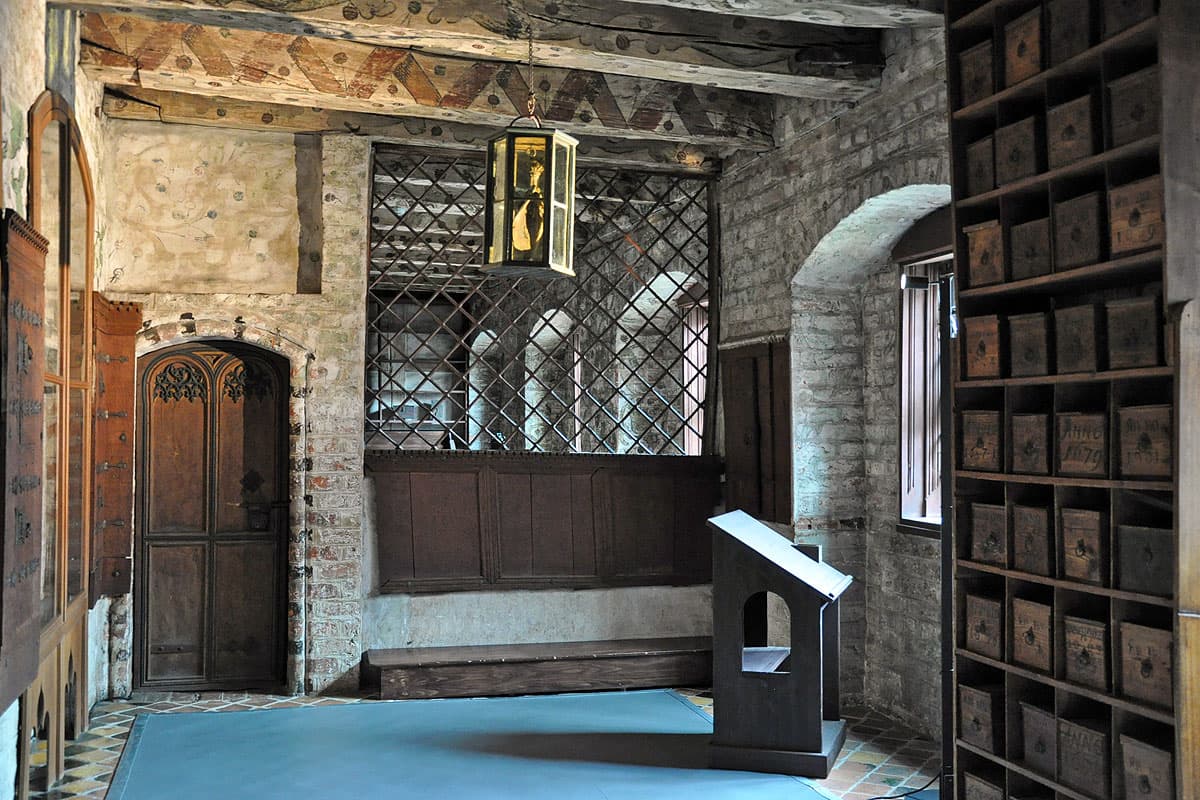

Die Wildsau wurde übrigens nicht gegessen, sondern zum Dank aufbewahrt. In der Alten Kanzlei des Lüneburger Rathauses kann man in einem gläsernen Kasten noch heute den Schulterknochen der Salzsau bewundern.